Robert Longo in a ‘Storm of Hope' at Jeffrey Deitch LA

By Tom Pazderka

A number of things played well into my visit to Robert Longo’s exhibition of recent works at Jeffrey Deitch in Los Angeles that made the entire experience haunting, cinematic and strangely familiar. Arriving in a Los Angeles still in the midst of protracted Covid lockdowns paints a serene post-apocalyptic picture. Where in the past one would drive white-knuckled for hours through impenetrable traffic, fighting for every inch of car space only to park miles away and walk the rest to the intended destination, these days one can simply plop the car next to the gallery and walk in the way one would in places like Idaho or Baton Rouge.

With none of the terrible trappings of Los Angeles present, one gets to see what the city actually is, a hodge-podge of mixed up architectural stylings intended to traverse the hypothetical line beyond simple mimicry, pot-holed streets and gridded neighborhoods, small cities and townships, whose differentiated denizens and cultures, have since the middle of the 20th century smashed together into a patchwork of disjointed building styles and whose horizon seems to always be receding into some form of a utopic foreverland.

The experience inside the gallery itself felt very post-apocalyptic. Waiting behind the darkened double doors is a cavernous space with two front desks on either side, both with an armor of plexiglass completely surrounding the masked desk person behind it. No literature, no promotional material, nothing sits on the monolithic tables, a place where one is to go through the quick process of checking in. Everything is entirely hands-free. Scan a QR code, sign in. Google then collects your data and sends it to the NSA, then get your pdf flyer by scanning another code and you’re done. How futuristic. But we all ‘understand.’ It is still Covid, a year later, after all. It is a reality we all should’ve already gotten used to by now.

Southern California has been very windy the last few days, intense gusts bending trees, knocking over trashcans and blowing around the meager possessions that many Angelenos who are ‘experiencing homelessness’ did not manage to secure. Inside the gallery the howling winds rattling doors and pounding the roof, form an intense backdrop, an anxiety inducing soundtrack to the stark black and white monumental drawings inside. It is in some sense the perfect way to experience the exhibition because its goal is precisely to produce just this sort of anxious reaction to its content.

Robert Longo, installation view, Jeffrey Deitch Gallery. Photo by Tom Pazderka

I am here on a mission of sorts. A very dear friend of mine works for Robert Longo at his New York City studio and it is my task to figure out which of the drawings are ‘his,’ meaning, which drawings did he produce or work on? Robert Longo has a long and illustrious career that stretches far back into the heyday of the 1980s New York art world. It is here that he established himself, as a young upstart artist, with a series of drawings of floating figures in business attire, suspended in air like meat puppets, drawing (pun intended) on the growing class tension and anxious bravado of the Reagan era. Here at Deitch, Longo continues a similar yet different strain of thought with a new series of heroic-sized charcoal drawings.

Here are images of Robert E Lee statues ‘enhanced’ with graffiti, another one of a Lee statue being taken down by cranes in the middle of the night, sinking refugee boats, riot police facing off against protesters, Nazi swastikas painted on headstones in a Jewish cemetery, even a black and white rendition of a Jackson Pollock painting, all in charcoal. They are all too familiar and easily digestible. These drawings derive their power not from their content so much as from their almost messianic adherence to the medium. They seem to say, here is an artist, who despite his pessimism about the present and the future, in drawing very close and tenuous connections between grand historical events, nonetheless believes in the possibility of salvation through art, which makes this show much more optimistic than its monochromatic and austere atmosphere suggest.

Robert Longo, installation view, Jeffrey Deitch Gallery. Photo by Tom Pazderka

Storm of Hope is a title which is already suggestive that whatever negativity exists in the world around us, ultimately this all shall pass and will be replaced by some ambiguous, but brighter future. In other words, Build Back Better, as we collectively look, but may not necessarily arrive at an Obama 2.0 presidency with Joe Biden. The large anteroom that houses drawings of the Capitol, the Supreme Court and the White House surrounded by scraggly trees and a giant sinkhole in the foreground, still reads as the work of someone whose undying belief in the ‘idealism’ of America and its founding mythology trumps any kind of pedantic disagreement with the political morass of the last four years of Trumpism.

Longo is here a true modernist, dedicated not so much to the project as such, but to the emotional content by which it was propagated throughout the 20th century, with Jackson Pollock as the penultimate heroic symbol of American depressive monumentality. Pollock’s meteoric rise to fame and a breakneck crash and burn, bracketing the public life of one train wreck of a man whose personal demons haunt every account of his life, undergird much of the conversation being had on the floor of the exhibition.

There is much to the show that feels too heavy handed and clunky. The ‘monoliths’ with inscribed lettering in the middle of the main room are a prime example. References to iPhones and 2001 A Space Odyssey are so literal they slap one over the face with how little meaning they represent. On a superficial level seeing Longo’s exhibition is a bit like watching the last two Ridley Scott Alien films – they are terribly platitudinous, derivative and self-referential, but finely crafted, visually stunning, beautifully shot and indulge in all the ‘right stuff’ that true fans of his work want to see and ultimately will see, if only to complain about them afterward, in much the same way they complain about every Star Wars film ever produced since the late 1990s as they fork over dollars to Disney and George Lucas for their annual fix.

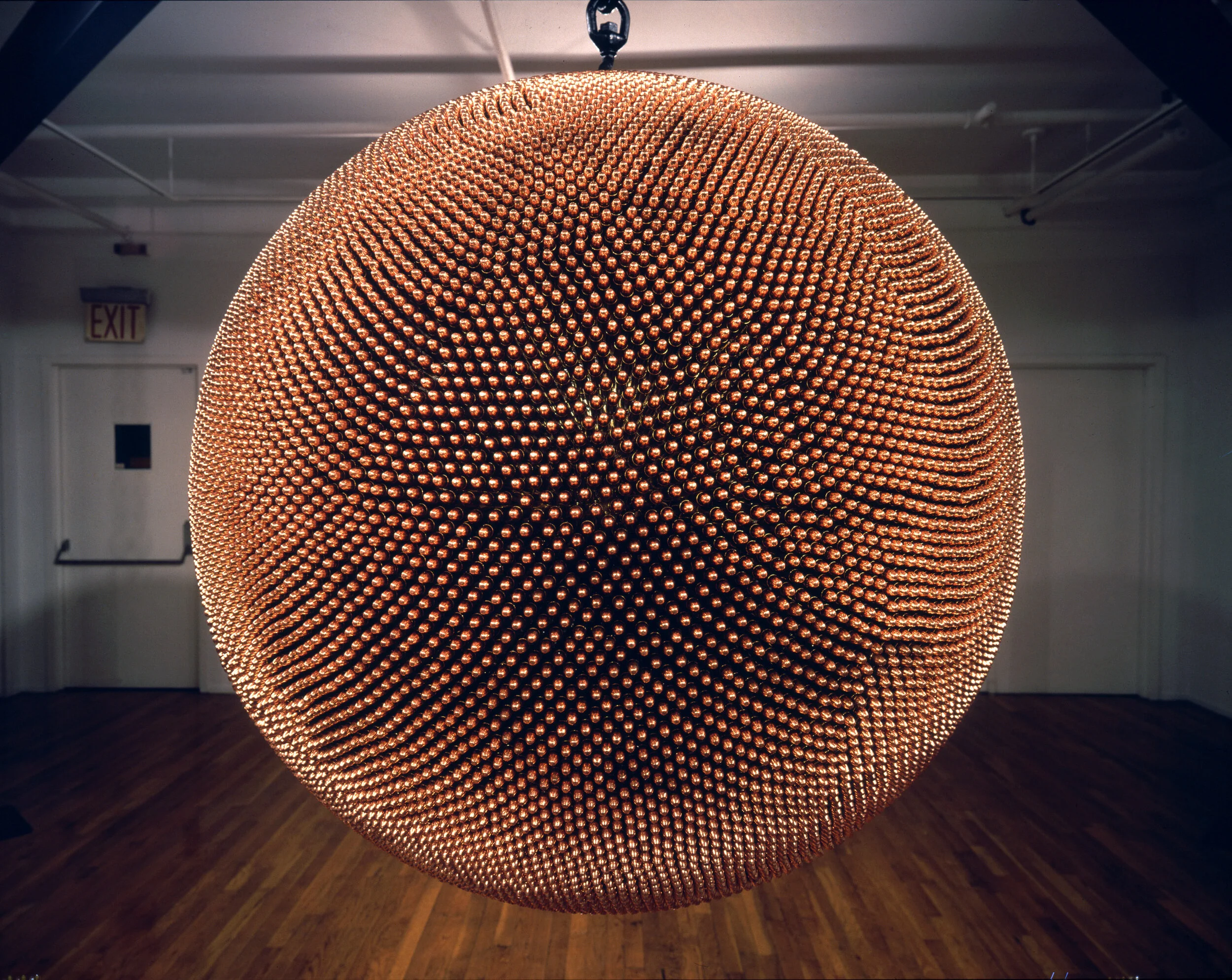

Ironically, or perhaps not, the work called “Death Star,” a giant metal sphere studded with forty thousand bullets, (yes, it’s that on the nose) was missing. Apparently, it never made the trip from New York, getting caught in a blizzard somewhere along the way after it was already late due to production issues. There is a video of it in the room where the rig that was meant to receive it stands and it does look rather impressive.

The main takeaway from the exhibition is that one cannot underestimate the enormity and scale of the drawings – their tightness of production and absolute commitment to aesthetic fanaticism – and of their appeal to the wider liberal and progressive (Democratic) audience. The danger, of course, is that by that same token, the images have a tendency to slip into a very soy-based, conservative take on the world, and to revel in schadenfreude rather than in analyzing our current predicament. There really is nothing wrong with producing and juxtaposing images of a kneeling football player, the face of a jaguar, and the three branches of the US government. In this context their literal reading, probably serve them better than if they were completely veiled in obscurity.

This sort of imagery just isn’t my cup of tea. There is an aura of creepiness to the black and white imagery, which I like and the howling wind perfectly underscored the suffocating political and social atmosphere out of which these drawings were borne. And Longo knows what sells. He does have a studio with many assistants and office staff to support him, my friend among them. His family and mortgage payment depend on Robert Longo getting to produce more of these drawings by the hour, by the day, by the week and selling them to some hedge fund for a hefty profit. It’s an amazing thing to see in real life and I hope he will get to do it for a long time. Apocalypse schmapocalypse.

Robert Longo, installation view, Jeffrey Deitch Gallery. Photo by Tom Pazderka

Cover: Death Star, 1993 18,000 brass and copper bullets, steel diameter of sphere: 36 inches (91.44 cm) steel frame: 106 x 213 inches overall (269.2 x 541 cm). Collection of the Burchfield Penney Art Center; Buffalo, New York.