Online Art Market: Managing What is Left of the (Art) World

Part 2 of the Hiscox Online Art Sales Report

By Tom Pazderka

2020 was a year most foul, no doubt. For millions, the lockdowns meant a complete reshuffling of daily life and an upending of things once thought to be as solid as Roman concrete. But not everyone suffered equally or suffered at all. The clear ‘winners’ in the new economy were the top people, top politicians, top brands, top artists and top galleries. Money flowed to the top in a way it has never done before, under the supervision of the elite donor classes. The 1% became the 0.1% and then the 0.0001%. Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs – now dead but still making a killing (pun intended) –and Elon Musk became the richest person on the planet, because people just couldn’t stop giving him money.

So how did the art world fare? As with the ‘recovery’ there are two, completely separate answers to this question. The first one is given by the Hiscox Report on Online Art Sales, while the second is delineated and analyzed in a 2020 book by David Deresiewitz The Death of the Artist and these are the answers. The digital (art) world has never been better, hotter or more volatile.

Upward price trends continued in the second half of 2020 as more people piled into online platforms. This makes sense because on the other side, the ‘real’ world, more or less ceased to be. For the artists themselves, 2020 meant a complete shutdown, cancelled exhibitions, cancelled or postponed gigs, cancelled income, cancelled careers, cancelled, cancelled, cancelled.

The move online wasn’t so much natural as it was inevitable, perhaps forced. Tens of thousands of artists moved to Patreon, opened up IndieGoGo and Kickstarter campaigns, applied to ever more diminishing public and private sources of funding. Thousands of artists have left cities like San Francisco and New York and set up shop in places like the Hudson River Valley in Upstate New York.

There is a lot of difference between numbers and sentiment, between metrics and individual experiences. Hiscox looks at data collected through surveys targeting online art sellers, this means that artists do not necessarily figure in their figures. The Death of the Artist looks at cold hard data but manages to foreground the artists through hundreds of interviews, because they are, unsurprisingly, why the art world exists in the first place.

But first let’s look at the good news. Last September, the second part to the Hiscox Online Art Sales Report was published, dedicated entirely to buyer behavior. Right from the start, the report is bullish on the online market, touting the online “transformation” as “quicker and more successful that anyone would have imagined.” No telling what is meant by the word successful in this context, but let’s continue. Art dealers, reflecting on the pandemic, usually ‘remark that the effects have not been as bad as they expected’ and believe, while the report shows, that “we have reached a watershed moment in the development of the online art market,” leaving the wide-open question, is consolidation next?

The report that follows, is a clear indication that consolidation is not only an ongoing trend, to some it is desirable. 55% of people that Hiscox surveyed purchased art online during the pandemic, “causing online auction sales to jump.” More than 82% of “of new art collectors had bought works online between March and September, up from 36% in 2019. 69% of millennial art enthusiasts, said they’d bought art online during the same period. 66% had bought between two and five artworks, while 7% have bought more than six pieces.”

Instagram had become the leading platform for online art, and 25% of those surveyed bought art through the Artist Support Pledge campaign, an effort in support of struggling artists. The report asks the pertinent question, is the switch to online permanent? The answer may be a ‘hybrid clicks-and-bricks model’ where artists, dealers and galleries continue to offer works and ‘experiences’ online in lieu of the real world. Translation, gentrification of all segments of the art world, both online and in the real world, is and will be an ongoing process, more money will be spent on fewer, more desirable brands and popular artists, because these are what sell, garner views, clicks and likes and ultimately these are what drives the market forward, while less and less money and attention will be given to experimental, interesting, offbeat, odd, subcultural artists because they pose a greater financial risk. More Warhols and Basquiats, more boring Art 21 propaganda, less Pussy Riot.

But the trend of the move online according to the report is best described in a triptych of charts. The first chart describes the number of art buyers that have bought art online since 2014, with an initial plateau at around 45% with a sharp rise in 2021 to 67%.

The second chart shows the average price per painting bought online since 2016. Across all categories, above $10K, above $25K and above $50K, 2020 meant an almost 10% increase in revenue. What is very interesting is that these figures point heavily in the direction of focus toward already established, already famous artists, because emerging artists almost never sell, and buyers almost never buy, their works above the $10K mark. These figures may also be pointing to a greater interest from buyers to purchase on the secondary market, where price inflation usually signals short and long term return on investment. The Hiscox report does point out that the chart is ‘supported by average prices in online-only auctions at Sotheby’s , Christie’s and Phillips, which jumped from $8000 in 2019 to almost $24,000 in the first eight months of this year’ (2020), thus indirectly proving the points raised above.

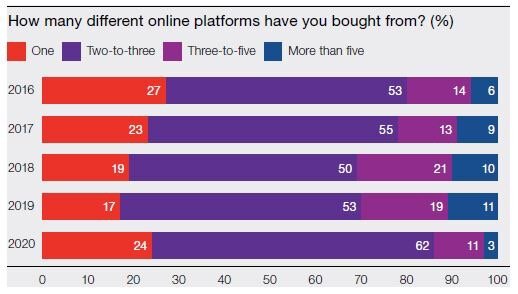

Chart three simply shows that change from 2016 to 2020 in the usage of social media for online art purchases. Simply put, ‘buyers are focusing on fewer online platforms’ which could mean ‘the consolidation in the online art industry is gathering pace.’ Online auction platforms garner more than half of online art shopping. Online auction sales at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips increased from $168 million to $597 million.

Interestingly however, the online platforms where emerging and mid-level artists predominate, have lost a little steam in 2020. While “new and younger buyers still prefer online marketplaces,” with 71% of new art buyers buying from the likes of Artsy, Artnet, Artspace, RiseArt or SaatchiArt. Over half (56%) of younger collectors also preffered these platforms, though that number was down from 2019 (66%). Consolidation begets domination.

Online art buying behavior is a strange animal. All of the old notions of why people buy art in the first place apply to it, such as identity and status, social aspects such as being part of the in-crowd and patronage, and the obvious one, return-on-investment, the standout from the pack was what Hiscox terms “compassionate consumption.” Nearly 96% of respondents cited ‘emotional benefits’ as motivation for purchasing work online during the lockdowns, which may amount to one of the major upsides among the many downsides to online commerce relative to the arts, because as we know, since the year 2000, digitalization had decimated the arts from music, to film, to visual art and beyond. Perhaps it is now trying to give something back.

The last section of the report dials in on Instagram as the clear winner in the social media visual art arena. Between 87% and 92% of art buyers use Instagram for ‘art-related purposes.’ While “most (87%) use it to discover new artists and to find art to buy (86%), making it an important selling platform for the art market.” Large art market players are all ‘using the ‘swipe-up’ function on their Instagram stories to link to their potential buyers. This fact is key because this function is unavailable to the vast majority of independent artists who use Instagram because there is a minimum follower limit that enables it.

Facebook lost clout in recent years and only about 23% of buyers use it now as their preferred social media to look for/at art. Interestingly, 73% of Hiscox survey respondents see artists as Instagram’s main influencers, giving rise to speculation that traditional models of galleries, museums and collectors are slowly slipping away, with the notion that artists now have the necessary tools to cultivate their own audiences and following without intermediaries.

The most interesting part of the report however is left for last. Artists especially should be paying attention. As expected, most buyers “look for paintings (74%), followed by prints (66%), photographs (44%), drawings (41%), sculpture (27%) and new media (21%).” Most paintings sold during the pandemic were in the price range $1,100 to $5,000.

And now, the bad news. One of the main problems with basing one’s finding on metrics and surveys is that this method completely ignores why art gets produced in the first place. It ignores what kind of art gets made and presupposes that since the numbers are going up, the signal must be that everything in the art world is just fine. New, challenging even subversive art is not part of such a scheme as everything is reduced to transactional relationships. Art reduced to metrics and data sets champions the ‘winners,’ whoever they may be at any given moment, it lionizes those who can outsell and outstrip the competition, and skews heavily in favor of the Jeff Koonses of the world rather than the small-time artists looking to piece together a living in a dying art world.

In his book, The Death of the Artist, William Deresiewicz analyzed these very problems facing the artists and the art industry as a whole. In the book Deresiewicz points out that while Silicon Valley types evangelize the benefits of social media, because of their vested financial interest and keeping users hooked, they have presided over the systematic dismantling of the art world and hacked away at the traditional models through which artists used to make a living. They did it by appealing to the artists’ emotions: ‘Can’t make a living as an artist anymore? You shouldn’t want to. Just do it on the side: just do it for love.’

The word ‘amateur’ derives from the French word for love; and social media has turned entire generations of artists into Balkanized networks of amateurs, all seeking to sell themselves and their wares to the millions of potential buyers, the carrot at the end of the stick that Silicon Valley evangelists use to get artists to sign up. Post stuff for free, then monetize it. It is the old trick that has been used with artists since time immemorial, the idea of ‘exposure’ gets conflated with payment and most artists tend to be willing to give their work away for the chance to get eyeballs on their work.

In other words, artists tend to work for free. This is the business model for the entire social media industry. Since the crash of the dot com bubble, artists have been slowly slipping away into lower class oblivion: “artists who are otherwise successful,” “who win a modicum of recognition – are unable to support themselves at a middle-class level.” The data is truly horrifying.

“From 2009 to 2015, fulltime writers saw their writing-related income decline by an average 30%. From 2001 to 2018, the number of people employed as musicians dropped by 24% due to file sharing software like Napster which rolled out in 1999. The music business peaked that year at $39 billion in global revenue. By 2014, that figure had fallen to $15 billion. From 2003 to 2013, the share of Americans who reported having attended a museum at least once in the previous year dropped by 20%.” And as of 2020, the budget of the National Endowment for the Arts came to all of $162.25 million, a figure that represents a decline of 66%, adjusting for inflation, since its peak in 1981, pencils out to roughly 49 cents per person, and amounts to less than a third of what the military spends on bands. Total government spending on the arts declined by 23% since 2001.

Thus, Silicon Valley swoops in for the rescue with its shiny digital platforms and visions of masses of followers monetized into channels of passive revenue streams. Crowdfunding, Spotify, Instagram, the sky is the limit. Hiscox may be bullish on the 2020 trend, but visions of grandeur tend to crash on the rocks of reality.

“On Patreon, according to a 2017 analysis, only 2% of creators bring in more than the federal minimum wage of $1,160 per month.” Internet fatigue had caused Kickstarter’s annual financial intake to plateau. “Of the 2 million artists on Spotify, less than 4% account for over 95% of streams.’ And of the entire 50 million song catalog that Spotify manages “20% have never been streamed.”

Is consolidation really what we should be looking forward to right now? Perhaps, if you’re one of the big three. The “big sucks the traffic out of small” and this is “why the internet itself inclines so strongly toward monopoly. Everybody uses Facebook because everybody uses Facebook (and Amazon and Google and YouTube, which is owned by Google, and Instagram, which is owned by Facebook.)”

In academia, once the last bastion of the independent artist, has also been stripped down to bare bones, as tenured positions, even fulltime positions, increasingly become a mirage. Less than 30% of teachers at US colleges are faculty professors. The vast majority are adjuncts, postdocs, graduate students and others. In the visual arts, the number is more like 6%. Fulltime positions regularly attract 200 applicants, sometimes as much as 800, and these positions pay peanuts.

There has been a truism making its way around American culture about Millennials that claims that the reason that this generation clings to ironic detachment, alienation, boredom and, above all, fatigue, is because their future has been slowly but surely foreclosed, leaving most in arrested development. A generation without hope for a brighter tomorrow, left groping in the darkness for any semblance of meaning, is said to be doomed and in permanent paralysis.

Millennials are the first generation in recent memory brought up by self-absorbed parents, whose diatribes on the efficacy of personal salvation through diet, fitness and mental health produced a reactive force with the only refuge the internet.

The problem isn’t so much that the future was slowly canceled, but rather that Western civilization had arrived at its doorsteps. After accepting the invitation to enter this most sacred space in which the marriage of life, politics, spirituality/religion and the internet anxiously meshed in a slurry of chaotic networks, chatrooms and message boards, what was meant to be a great revelatory experience turned out to be an ignominious shrug of the shoulders.

By the time Millennials became grown adults, their world had been overrun by corporations, banks and seething politicians. What was once touted as the shining horizon of freedom and creative expression had become a balkanized wasteland of commercial interests, CIA operatives and banal celebrity culture. The inner world of the internet had become a mirror of the outer world from which the millennials once sought to escape.

The future was thus forced onto the millennials rather than taken from them. In such a world where everything is seemingly available and effortless, a greater pressure on self-actualization is exerted on individuals than ever before. This is where the digital demigods tend to step in. They offer visions of a brighter future but cover up the fact that we are already enmeshed in it. The point of social media is to monetize and manage its human resources. The pandemic had shown in real time what that management would look like as more and more people came online and lived their lives entirely behind the shimmering screen.

The art world is a very tiny part of the entirety of online commerce, but artists have as a rule been the litmus test for where society tends to be headed. There is at least one more positive takeaway from the Hiscox report that I have saved for last. It appears that humanity is in no way looking to switching entirely online. Despite the pandemic, people continue to depend on the real world for their experiences and thus “the online art market will continue to depend on the physical infrastructure in creating trust and encouraging online sales.”