Studio Visit: Nathan Hayden

At first, moving from Nathan Hayden’s wall drawings to his recent sculptural work feels uneven—the dramatic torque of his large scale black and white geometric abstractions is replaced by a softly lit stasis, singular shapes, subdued hues—but the leap lets you see the development of Hayden’s haptic techniques, his study of positive and negative space, and his affinity for imperfections.

You also see the way his geometric forms and often surprising drips, textures and fingerprints, align early modernist abstraction with hippy vibes and aesthetics pulled from nature. Nowadays, you’ll find Hayden working in his Santa Barbara home which he shares with his wife, artist Hannah Vainstein, and their daughter Zadie. But some time ago, in the early 1980s, Hayden was a young boy, growing up in rural West Virginia with his parents, unofficial subscribers to the back-to-the-land movement. Hayden’s family had no running water and lived in a log cabin that his dad built with the help of a borrowed donkey to haul chopped down trees.

Nathan Hayden in his Santa Barbara studio. Photo by Debra Herrick

“That’s where I spent the first eight years of life,” says Hayden. “Our friends were craftspeople and artists, people who were thinking about aesthetics, making things with their hands and integrating art and life; it was a countermovement to the Industrial Revolution.” In 2015, the Walker Museum called it “Hippie Modernism” in their exhibition of the same name. It was “alternative communities and new ways of living and working together,” write the curators, “... a search for a new kind of utopia, whether technological, ecological or political, and with it a critique of the existing society.” This is Hayden’s lineage.

In Hayden’s wall drawings, he circles a singular motif, “usually some form I’m looking at, the bark of trees, the landscape, the positive/negative spaces between rocks or branches,” he says. Before starting a new piece, he makes “the cards,” small studies that he’ll use to find a geometry that can unfold in different patterns and directions.

Nathan Hayden, You Shift Your Vibage and You Shift Your Vibage Back, detail, ink on wall

Cards by Nathan Hayden in his studio. Photo by Debra Herrick

There are elements in his work that reference the folk art tradition, Gee’s Bend quilts, Navajo weaving and Japanese wood block prints, and at the same time, op art. Its work made in the space between outsider and insider—the boy in West Virginia’s back country, and the MFA teaching art to college students.

Patterns, for Hayden, are access points to spirituality, what his younger sci-fi reading self called other dimensions. He finds many of his patterns in nature while dancing. As he walks or dances outside and in nature, material images appear to him. “For me, ideas are culled from things that are interior and exterior,” he says.

“Looking at rock forms and tree forms and flowers and then I’m thinking about them a lot. The dancing has to do with the spacing and how to represent what I see in nature in my own terms—I haven’t totally figured out how to express it with language. Dancing just makes my mind more pliable. The movement unsticks me.”

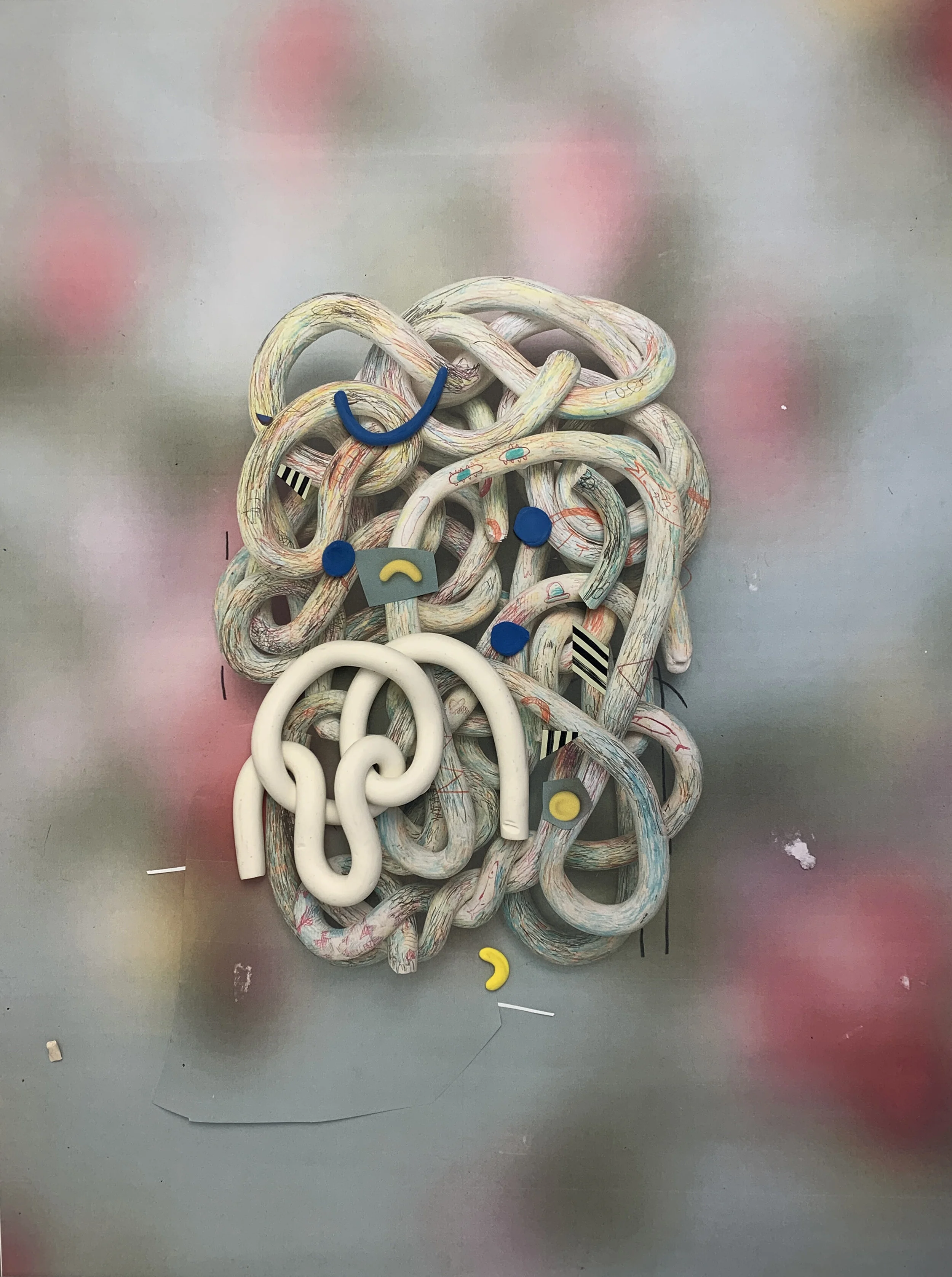

Recent sculptural work in Hayden’s studio. Photo by Debra Herrick

Recent sculptural work in Hayden’s studio. Photo by Debra Herrick

From dancing, Haydan finds patterns and shapes that echo the forms he sees in trees and rocks. He then hand builds his pared down pink clay sculptures. The fingerprints he leaves on each one are registers of his hand, traces of time and work. But they’re also an invitation to touch something textured and naturally fibrous, something other than a screen, plastic or other mass-produced artifact.

“When Zadie began to talk, she learned the word ‘sculpture’ and it became a loose term for ‘object,’ but always a textural object,” says Hayden. “I’m searching for some kind of continuum between those natural objects that are in our everyday lives and these sculptures.”

Nathan Hayden’s studio. Photo by Debra Herrick

Nathan Hayden, What Was Magic of Numbers, Hypnotic & Wonders, ink on wall, 12 x 44 ft.

That continuum between the natural world and the haptic artistic practice Hayden has cultivated is made up of his background, studies and practice, and is clearly seen in his admiration of turn-of-the-century artist Charles Burchfield, who was the first artist to have a solo exhibition at the MoMa in 1930. Burchfield created his watercolors of nature scenes and townscapes immersed in the rural landscape and forests of upstate New York.

His belief in “the healthy glamour of everyday life” resonates with Hayden and his work—“something about the subtle glamor of everyday life,” says Hayden, “that’s sort of how I see it now, the world and nature and the wonder of being in that.”

This article was originally published in Lum’s Winter 2021 print magazine.

Nathan Hayden in his studio. Photo by Debra Herrick

Nathan Hayden, How the Medicine Sees, ink on wall

Cover: Nathan Hayden, Strong Magic, painting on wall and sculptures